Excellence In Clinical Supervision Practice

Effective professional training relies heavily on the quality of clinical placements. Within the field of clinical psychology, trainees typically complete four to six placements, the first of which is conducted within a university-based clinic. Clinical supervisors are the front line of professional training, ensuring that trainees acquire the necessary knowledge, and develop the broad range of competencies required to practice.

As “gate-keepers” of the profession, supervisors carry a great deal of responsibility. As a consequence, our team of clinic directors and researchers is committed to supporting supervisors by developing best-practice tools and protocols that are evidence-based and consistent with current models of professional training.

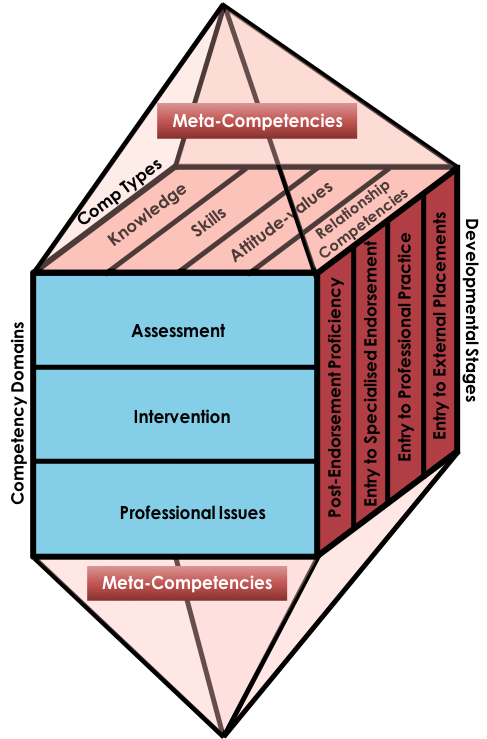

Competency-Based Model of Professional Training

With a research driven strategy, our team has been committed to promoting and integrating a competency-based model of supervision into practice. Competency-based supervision posits that an established framework of competencies should serve as a blue-print to inform the content of the curriculum and drive practitioner training and clinical supervision. The model recognises that practitioner competence includes knowledge, skills, attitude-values and general relationship competencies contribute to in-practice clinical competencies. These competency-types inform training strategies and goals, and to direct teaching and supervisory methods. In addition, a competency-based approach provides supervisors with end-point targets to evaluate trainees according to criterion-referenced standards that are consistent with evidence-based practices and endorsed by regulatory authorities (e.g. Psychology Board of Australia), and relevant professional bodies.

Competency Crystal

Craig Gonsalvez, Trevor Crowe & Mark Donovan (2017)

At its core, the model acknowledges that:

- competency frameworks can be conceptualised as multi-dimensional with each dimension comprising multiple domains (e.g., assessment, intervention, professionalism)

- co-existing competencies can exhibit different developmental trajectories

- competencies can vary from basic to advanced competencies that involve complex and integrative thinking, reasoning, judgment, skills and behaviours

- manifest capabilities can be driven by competency-types (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitude-values and relationship competencies)

- higher-order meta-competencies can underpin, direct and mediate the acquisition and enhancement of competence

- trainees and practitioners follow a developmental trajectory towards the attainment of competence

- this developmental trajectory may be non-linear and context specific

The competency-based model has been critical in informing cross-disciplinary supervision practices, and it has been central in driving changes in training method and assessment strategies both in Australia and internationally. Our research team has been at the forefront of this emerging pedagogical approach, spearheading research initiatives, and implementing competency-based supervision strategies at a systemic level.

Promoting and Fostering Excellence

New developments in supervision theory and practice have highlighted a growing recognition of the importance of supervision on the acquisition and maintenance of professional competence. This has led to a greater scrutiny of supervisory practice, and to positive change. The need to better understand current supervision practices is paramount, particularly given the mandatory requirements for supervisor training and registration.

Our team is dedicated to conducting and disseminating research that sheds light on the efficacy of, and barriers to, good supervisory practice. Our broad goal is to lead the way towards a systemic adoption of empirically-validated supervision practice, ensuring that future clinical psychologists represent the profession by performing at a level of competency that is expected by registration boards, employers, clients, and the general public.

In 2013, our University of Wollongong partners (funded by Health Workforce Australia) produced a psychology supervisor training video/DVD that addresses the following:

- Designing a competency-based plan for supervising: Establishing SMART goals

- Identifying types of competency and suitable supervision methods to facilitate competency enhancement

- The use of observation methods in supervision: Dealing with resistance

- Re-establishing goals: Working with resistance

Curriculum Design for Supervisor Training

The popularity of competency-based pedagogies has underpinned important changes to supervisor training across disciplines, nationally and internationally. Unlike past practices where experience in clinical practice was deemed sufficient to qualify practitioners for supervisory practice, currently, supervisors in psychology are required to demonstrate supervisory competence in accredited training programs approved by the Psychology Board of Australia.

Key members of our team have been instrumental in designing and delivering the supervisor training curriculum for the Australian Psychological Society Institute (APSI). Consistent with a competency-based model, the 20-hour training program requires supervisors to demonstrate (1) knowledge of the competency-based pedagogical model, and its implication on supervision practice, (2) proficient supervision skills, (3) appropriate attitude-values (e.g. ethical values, reflectivity), and (4) necessary relationship competencies (e.g. alliance).

The nationally consistent Guideline for supervisors and supervisor training providers is critical, as supervisors are gate-keepers of the profession, and undertake the responsibility for ensuring that trainees have met competency benchmarks as they begin their careers.

Systematic Evaluation of Trainee Competence

Consistent with the competency-based model, it is critical that trainees are assessed so that competencies are captured across domains and competency-types. To do this, competencies must be demonstrated through outputs, outcomes, and performance in ecologically valid contexts. These may include role-plays, observation, co-therapy, case reports and discussions, and evident professional conduct. To quantitatively and objectively measure competency growth, standardised and developmentally appropriate assessment are essential but lacking.

Our team has strongly advocated for standardisation of trainee evaluation, and through our research endeavours, we have sought to (1) develop clear criteria of competence across the developmental trajectory, (2) isolate developmental trajectories that indicate under-performance, (3) build normative data sets that institutions can use for benchmarking, (4) identify barriers to the successful implementation of competency-base supervision practices and assessment, (5) thoroughly evaluate the existing assessment instruments, and (6) develop novel approaches to assessment.

In addition, we have worked closely with Australian and international institutions to develop a standardised online assessment tool that is now being used by more than 24 institutions.

Design of Assessment Tools for Evaluating Trainee Competence

The valid and reliable measurement of competence is critical to effective supervision, and to the credentialing of psychologists. Despite this, there is compelling evidence that commonly used assessment tools are vulnerable to leniency and halo biases. Likert-based rating scales are particularly prone to both leniency and halo biases.

Consistent with competency approaches, there is a strong need for the development of new assessment tools that require performance of trainees to be evaluated against a predetermined standard (e.g., professional conduct and practice that will be deemed adequate, acceptable and effective) rather than merely be ranked in comparison with peers.

Our team continues to make valued and internationally acclaimed contributions to competence assessment by improving existing assessment tools, and developing novel approaches (e.g. the vignette-matching assessment tool or V-MAT).

Design of Assessment Tools for Evaluating Clinical Supervision

In addition to the need for better instruments to assess trainee competence, there is also a dearth of measures to evaluate supervisory competence. Systematic evaluation of supervision and supervisor competence by supervisees accrued over several years has helped better understand the nature and clustering of these independent competencies. We have recently published the Supervisory Evaluation and Supervior Competence (SE-SC) scale that provides scores on two overall domains (Supervision Satisfaction and Supervision effectiveness) and nine subscales: Caring and Support, Supervsior Expertise, Planning and Management, Goal-directed Supervision, Restorative Competencies, Facilitation of Reflective Practice, Summative Assessment Competencies, Group Supervisory Competence, and Facilitation of Psychological Testing competence (See Gonsalvez et al., 2018) The instrumentcan be used by trainees to evaluate the supervision they receive and by supervisors themselves as a measure of self-evaluation. The profile of scores across the subscales provides feedback to individual supervisors that is formative and constructive.

Please contact us if you would like more information about our assessment tool for evaluation clinical supervision.

Our Clinical Supervision Research

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

- Blackman, R., Deane, F., Gonsalvez, C. and Saffioti, D. (2017). Preliminary exploration of psychologists' knowledge and perceptions of electronic security and implications for use of technology-assisted supervision, Australian Psychologist, 52(2),155 - 161.

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Wahnoon, T., Deane, F.P. (2017). Goal-setting, Feedback, and Assessment Practices Reported by Australian Clinical Supervisors. Australian Psychologist, 52, 21-30. doi: 10.1111/ap.12175

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Deane, F. P., & O'Donovan, A. (2017). Introduction to the Special Issue Recent Developments in Professional Supervision: Challenges and Practice Implications. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 83–85. doi:10.1111/ap.12276

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Hamid, G., Savage, N. M., & Livni, D. (2017). The Supervision Evaluation and Supervisory Competence Scale: Psychometric Validation. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 94–103. doi:10.1111/ap.12269

- Morris, E. M. J., & Bilich-Eric, L. (2017). A Framework to Support Experiential Learning and Psychological Flexibility in Supervision: SHAPE. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 104–113. doi:10.1111/ap.12267

- Nicholson Perry, K., Donovan, M., Knight, R., & Shires, A. (2017). Addressing Professional Competency Problems in Clinical Psychology Trainees. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 121–129. doi:10.1111/ap.12268

- Stevens, B., Hyde, J., Knight, R., Shires, A. & Alexander, R. (2017). Competency-based training and assessment in Australian postgraduate clinical psychology education, Clinical Psychologist, 21(3), 174-185.

- Gonsalvez, C., Brockman, R. and Hill, H. (2016). Video feedback in CBT supervision: review and illustration of two specific techniques, The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 9, E24. doi:10.1017/S1754470X1500029X

- Shires, A., Vrklevski, L., Hyde, J., Bliokas, V., & Simmons, A. (2016). Barriers to provision of external clinical psychology student placements. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 140–148. doi:10.1111/ap.12254

- Terry, J., Gonsalvez, C., & Deane, F. P. (2017). Brief Online Training with Standardised Vignettes Reduces Inflated Supervisor Ratings of Trainee Practitioner Competencies. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 130-139. doi:10.1111/ap.12250

- Cartwright, C., Rhodes, P., King, R. & Shires, A. (2015). A Pilot Study of a Method for Teaching Clinical Psychology Trainees to Conceptualise and Manage Countertransference, Australian Psychologist, 50, 148-156.

- Deane, F. P., Gonsalvez, C., Blackman, R., Saffioti, D. and Andresen, R. (2015). Issues in the Development of e-supervision in Professional Psychology: A Review. Australian Psychologist, 50(3); 241–247. doi: 10.1111/ap.12107

- Gonsalvez, C.J., Deane, F.P., Blackman, R., Matthias, M., Knight, R., Nasstasia, Y., Shires, A., Nicholson Perry, K., Allan, C., Bliokas, V. (2015). The hierarchical clustering of clinical psychology practicum competencies: A multisite study of supervisor ratings. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 22, 390-403. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12123

- Hill, H., Crowe, T., & Gonsalvez, C.J. (2015). Reflective dialogue in clinical supervision: A pilot study involving collaborative review of supervision videos. Psychotherapy Research. DOI:10.1080/10503307.2014.996795

- Gonsalvez, C.J., Deane, F.P., Caputi, P. (2015). Consistency of supervisor and peer ratings of assessment interviews conducted by psychology trainees. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. DOI: 10.1080/03069885.2015.1068927

- Gonsalvez, C. and Calvert, F. (2014). Competency-based models of supervision: principles and applications, promises and challenges. Australian Psychologist, 49(4), 200 - 208.

- Gonsalvez, C.J., & Crowe, T. (2014). Evaluation of Psychology Practitioner Competence in Clinical Supervision. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68(2), 177-93.

- Bushnell JA, Gonsalvez CG, Blackman R, Deane F, Bliokas V, Nicholson-Perry K, Shires A, Nasstasia Y, Allan C, and Knight R, (2013). Assessing ourselves: Is the assessment of performance in Clinical Psychology field placements due to biased raters or defective rating instruments Journal of the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists 23(3), 1-9.

- Gonsalvez, C. J., et al. (2013). Assessment of psychology competencies in field placements: Standardized vignettes reduce rater bias. Training and Education in Professional Practice, 7, 99-111.

- Livni, D., Crowe, T. and Gonsalvez, C. (2012). Effects of supervision modality and intensity on alliance and outcomes for the supervisee, Rehabilitation Psychology, 57(2), 178 - 186.

- Baillie, A. J., Proudfoot, H., Knight, R., Peters, L., Sweller, J., Schwartz, S. and Pachana, N. A. (2011). Teaching Methods to Complement Competencies in Reducing the “Junkyard” Curriculum in Clinical Psychology. Australian Psychologist, 46, 90–100.

- Britt, E., & Gleaves, D. H. (2011). Measurement and Prediction of Clinical Psychology Students' Satisfaction with Clinical Supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2),172-182.

- Gonsalvez, C. and Milne, D. (2010). Clinical supervisor training in Australia: a review of current problems and possible solutions, Australian Psychologist, 45(4), 233 - 242.

- Gonsalvez, C. (2008). Introduction to the Special section on clinical supervision', Australian Psychologist, 43(2), 76-78.

- Gonsalvez, C., Hyde, J., Lancaster, S. and Barrington, J. (2008). University psychology clinics in Australia: their place in professional training, Australian Psychologist, 43(4), 278–285.

- Gonsalvez, C. and McLeod, H. (2008). Toward the science-informed practice of clinical supervision: the Australian context, Australian Psychologist, 43(2), 79 - 87.

- Gonsalvez, C. J., & Freestone, J. (2007). Field supervisors' assessments of trainee performance: Are they reliable and valid Australian Psychologist, 42, 23-32.

- Gonsalvez, C.J., Oades, L., & Freestone, J. (2002). The objectives approach to clinical supervision: Towards integration and empirical evaluation. Australian Psychologist, 37 (1), 68-77.

- Gonsalvez, C. (2014). Establishing supervision goals and formalizing a supervision agreement: A competency-based approach. The Wiley International Handbook of Clinical Supervision, Wiley-Blackwell 9781119943327.